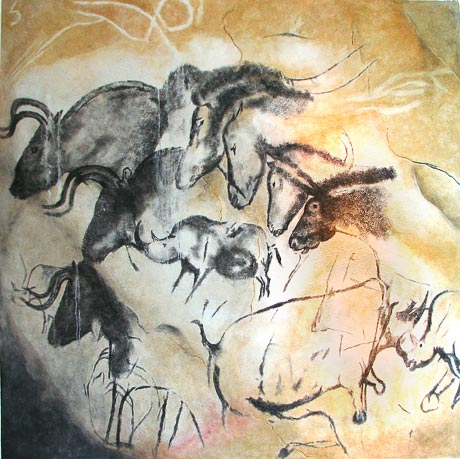

Wassily Kandinsky, Composition VIII, 1923, oil on canvas--

today this image quickly became our posterchild for Elements of Design

In high school, my European History teacher, the famous and infamous Betty Seizenger strode around the room looking over our shoulders. She remains the only 60 year-old woman I've know who could wear a snug black leather skirt and tall spike-heeled boots with style and grace, and as if no one should feel surprised. At the top of her warbly high-pitched voice (think Julia Child), she'd chortle "Form and Content, Form and Content! Lack one; you have nothing." Under threat of her (figurative) whip, I experimented with ferocious turns of phrase that would demonstrate the violence of the battle that I sought to describe in my essay; for another assignment I created a black box that you could cram your hand into, inside of which dull nails pushed into your skin to demonstrate the horror of a medieval prison. I can't think about form and content without thinking of Betty, and how fiercely she fought for their union.

Here's Betty Seizenger prostrate on the ground with one of her AP European classes. A couple years before me. I don't really know how form and content come together here, but they did achieve a nice pyramidal composition.

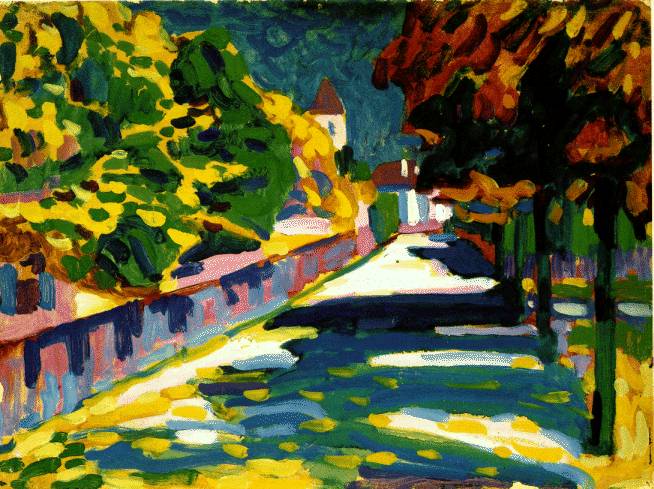

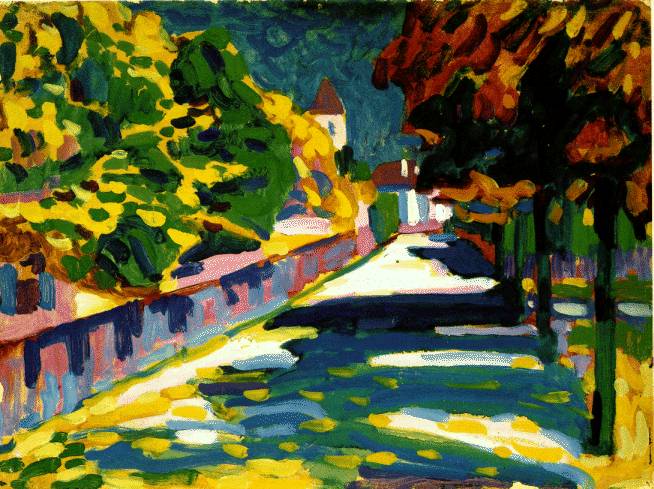

In class today, we talked about the most basic terms to describing the form of a work of art-- or it's formal qualities, as you'll hear me say. I chose a painting by Kandinsky to help introduce a conversation on these topics largely because Kandinsky wanted to see what would happen when he asked the form to become the content. Kandinsky does not control the interpretation of his work-- he gives that task to the viewer. He just controls the lines, colors, shapes, forms, textures, and tones.

I hope that you, too, will experiment freely to find ways of expressing ideas in words and pictures that work for you. I hope that you will learn to think of form and content as always supporting each other to achieve the most powerful expression. In the case of Kandinsky, the paintings achieve power through their evocation of content, rather than their explanation of it. One of you asked whether Kandinsky had always worked in this

nonrepresentational or

nonobjective style. He didn't, but he always used some degree of abstraction, even when representing houses or landscapes in his earlier works.

Kandinsky wrote: Kandinsky wrote: "Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the harmonies, the soul is the piano with many strings." We also talked about Synesthesia. MIT has started a

website to gather and share information about synesthesia, including some very brief but interesting anecdotes from synesthetes, and a 'virtual synesthesia' experience.

Here, Karen Chenauskydescribes the experience of seeing the colors of letters in quiet moments. If you get interested in Kandinsky and synesthesia, you might read this article. I said in class that Kandinsky studied the matter, but was not himself a synesthete.

This article says that he did. A little more searching-- just online-- tells me that some people think he was, some do not. Someone can research the matter, if you want!

Here's a link to a site that lays out the elements and principals of design clearly and correctly. Make sure you master these basics. They will remain with us all year.

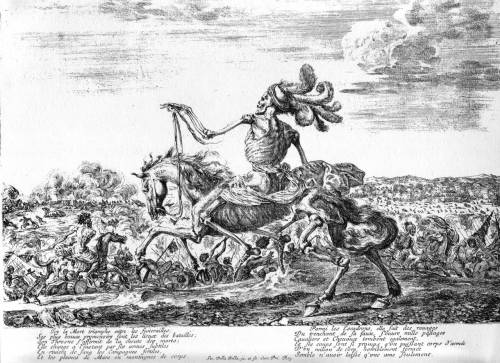

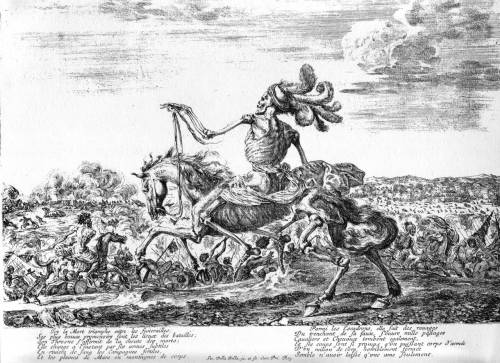

Today, we talked about portrayals of Death as a character... an

allegorical figure, looking at two very different images. You had great comments about them!

Here's a link to an article that discusses the important role Rousseau's

War played in Picasso's development of War imagery.

Henri Rousseau, War, 1894, Paris

Henri Rousseau, War, 1894, Paris Stefano della Bella, The Triumph of Death on the Battlefield, 17th century

Stefano della Bella, The Triumph of Death on the Battlefield, 17th century Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937

eting youth of folks the age of most of the people I teach.

eting youth of folks the age of most of the people I teach.